Introducing Machine Learning for Software Engineers!

Get hands-on with machine learning engineering

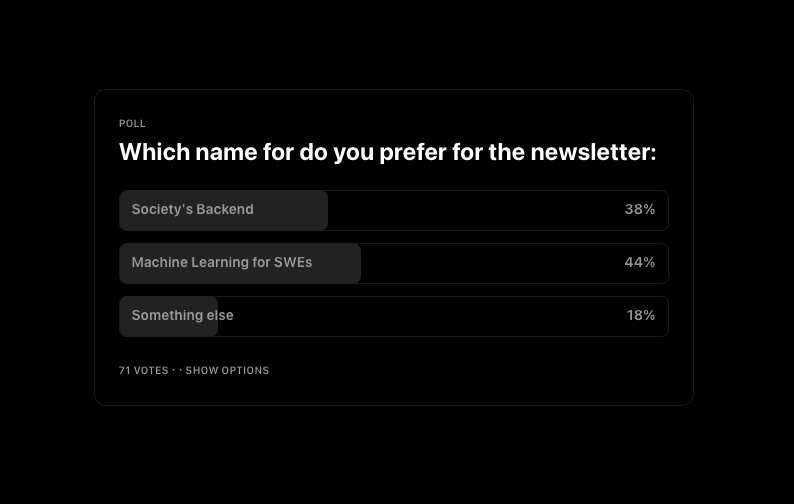

You might have noticed a name change recently: Society’s Backend is now Machine Learning for Software Engineers!

This change comes from some feedback I got from all of you (see below) and is meant to more clearly state what the newsletter is about and the benefit readers will get from it. This will help our community grow and our discussions find the right audience.

I’ll answer all your questions/concerns and explain everything below!

What is “Machine Learning for Software Engineers”?

Functionally, it’s no different from Society’s Backend. I’ll still be writing about the things I always do—real-world machine learning and what it means to build it. So the newsletter will be the same topics, but with more of an emphasis on showing instead of telling.

To do this, I’ve set up a Machine Learning for Software Engineers repo! You can find it at https://src.mlforswes.com. This encompasses the ML Roadmap many of you have already used and it will include the guides for building real-world ML systems end-to-end that will be coming out this year.

This packages all the sources you need to get hands-on with machine learning engineering into one nice package. To summarize:

The newsletter will remain fundamentally unchanged just with more of an emphasis on showing instead of telling.

We now have a community repo that will contain all sources to make showing easier.

Star the repo to get updates as projects are added to the repo and support me.

But I’m not a software engineer…

Don’t worry! Everything regarding the newsletter will remain the same. I’ll still explain real-world ML concepts plainly and you can still enjoy reading those articles.

The only difference is there will be supplementary code examples, but they will not be required to understand the content in the newsletter.

What’s happening to Society’s Backend?

Society’s Backend is actually remaining unchanged. My intention with the name “Society’s Backend” wasn’t really for it to be a newsletter. In my mind, Society’s Backend is the group of people building the technology society runs on. In other words, Society’s Backend has always been all of you, the readers.

Functionally, this means societysbackend.com will redirect to mlforswes.com preserving the path and query strings. We’ll see what the actual names ends up being used for in the future (no plans currently).

What does this mean for me right now?

Not much. It means the name of this newsletter will be different and there’s a repo to accompany it. It also means you’ll see graphics change from reading “Society’s Backend” to “ML for SWEs” or “Machine Learning for Software Engineers”. I’ll be going through and taking care of that over time.

I’ve also amended my pinned post for the newsletter to better reflect the direction we’re going. You can check it out here:

If you’re new to Machine Learning for Software Engineers, subscribe to get articles directly in your inbox and join us as we build things with machine learning.

Thanks for reading!

Always be (machine) learning,

Logan

The best way, in my view, to understand a field is to understand the reason why the field exists in the first place, Why do we need a field like machine learning? In short, what problems does it solve and why?

Let’s start with an analogy, something you do practically every morning: you wake up and get ready to go to work. What problems do you need to solve? For one, you need to put on some clothes to protect your body from the weather and your feet against the rough surfaces you might encounter. You need to perhaps cover your head with a hat or a scarf and protect your eyes with sunglasses against the harsh rays of the sun. These are the problems we need to solve in getting dressed.

Algorithms are like clothes and shoes, hats and scarves and sunglasses, continuing the analogy from above. You could wear sneakers, dress shoes, or high heels. You could wear a T-shirt, a dress shirt, a full length skirt and so on. Clothes and shoes are ways to solve the problem of dressing up for work. Which clothes you wear and what shoes you put on may vary, depending on the occasion and the weather. Similarly, which machine learning algorithm you use may depend on the problem, the data, the distribution of instances etc. The lesson from the fashion industry is quite apt and worth remembering. Problems never change (you always need something to cover your feet), but algorithms change often (new styles of clothes and shoes get created every week or month). Don’t waste time learning fashionable solutions when they will become like yesterday’s newspaper. Problems last, algorithms don’t!

There’s a tendency, unfortunately, of recommending universal solutions to machine learning these days (e.g., learn TensorFlow and code up every algorithm as stochastic gradient descent using a deep neural net). To me, this makes just about as much sense as wrapping yourself up in your bedsheets to go to work. Sure, it covers most parts of your body, and probably could do the job, but it’s a one size fits all approach that neither shows any style or taste, nor any understanding of the machine learning (or dressing) problem.

The machine learning community has spent over four decades trying to understand how to pose the problem of machine learning. Start by understanding a few of these formulations, and resist the temptation to view every machine learning problem through a simplified lens (like supervised learning, one of dozens of ways of posing ML problems). The major categories include unsupervised learning, the most important, followed by reinforcement learning (learning by trial and error, the most widely prevalent in children after unsupervised learning), and finally supervised learning (which occurs rather late, because it requires labels and language, which young children mostly lack in early years). Transfer learning is growing in importance as labeled data is expensive and hard to collect for every new problem. There’s lifelong learning, and online learning, and so on. One of the deepest and most interesting areas of machine learning is the theory of probably approximately correct (or PAC) learning. This is a fascinating area, which looks at the problem of how we can give guarantees that a machine learning algorithm will work reliably or will produce a sufficiently accurate answer. Whether you understand PAC learning or not tells me if you are a ML scientist, or an ML engineer.

The most basic formulation of machine learning, and the one that gets short shrift in many popular expositions, is learning a “representation”. What does this even mean? Take the number “three”. I could write it using three strokes III, or as 11, or as 3. These correspond to the unary, binary, and decimal representations. The latter was invented in India more than 2000 years ago. Remarkably, the Greeks, for all their wisdom, never discovered the use of 0 (zero), and never invented decimal numbers. Claude Shannon, the famed inventor of information theory, popularized binary representations for computers in a famous MS thesis at MIT in the early part of the 20th century.

What does it mean for a computer to “learn” a representation? Take a selfie and imagine writing a program to identify your image (or your spouse or your pet) from the image. The phone uses one representation for the image (usually something like JPEG, which is mathematically called the Fourier basis). It turns out this basis is a terrible representation for machine learning. There are many better representations, and new ones get invented all the time. A representation is like the material that makes up your dress. There’s cotton and polyester and wool and nylon. Each of these has its strengths and weaknesses. Similarly, different representations of input data have their pros and cons. Resist the temptation to view one representation as superior to all the others.

Humans spend most of their day solving sequential tasks (driving, eating, typing, walking, etc.). All of these require making a sequence of decisions, and learning such tasks involves reinforcement learning. Without RL, we would not get very far. Sadly, all textbooks of ML ignore this most basic and important area, to their discredit. Fortunately, there are excellent specialized books that cover this area.

Let me end with two famous maxims from the legendary physicist Richard Feynman about learning a topic. First, he said: “What I cannot create, I do not understand”. What he meant that unless you can recreate an idea or an algorithm yourself, you probably haven’t understood it well enough. Second, he said: “Know how to solve every problem that has already been solved”. This second maxim is to make sure you understand what has been done previously. For most of us, these are hard principles to follow, but to the extent you can follow them, you will find your way to complete mastery over any field, including machine learning. Good luck!

That’s awesome! I am into learning more about machine learning engineering 🚀🔥